Stink Bug Infestation of Dwellings

ENTFACT-654: Stink Bug Infestation of Dwellings | Download PDF

By Michael F. Potter & Ric Bessin, Extension Entomologists

Epic numbers of stink bugs invading homes and buildings were first reported in the mid-late 1990s. Although stink bugs live primarily outdoors, a variety known as the brown marmorated stink bug, can be a major nuisance when they enter buildings in search of overwintering sites. In many areas of the U.S. including Kentucky, these autumn invasions are such a nuisance that they affect quality of life.

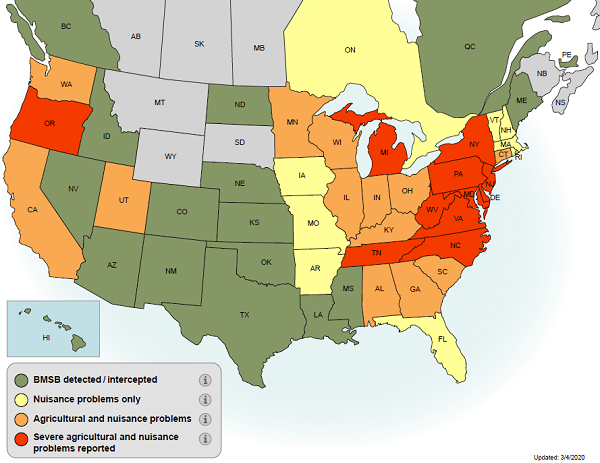

WHERE DID THEY COME FROM? The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB), Halyomorpha halys, is native to China, Taiwan, Japan and Korea. The pest entered the United States accidentally, possibly in shipping containers. Infestations were first noticed entering homes in Pennsylvania in the mid-1990s. Specimens were initially mistaken for a native stink bug variety, but later were confirmed as an invasive species from Asia. By 2005, the bugs had been detected in most mid-Atlantic states (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, West Virginia) as well as Washington and Oregon. Today, BMSB is present in at least 46 states and 4 Canadian provinces. Brown marmorated stink bug adults are strong fliers, capable of dispersing more than a mile. The bugs also are adept hitchhikers and are being transported place to place on vehicles and through commerce.

Current U.S. distribution and pest status of brown marmorated stink bug. Problems related to being a nuisance (structural) pest are greatest in states denoted by red or orange, followed by yellow. While BMSB has been detected in states marked in green, invasion of buildings has not yet been reported. A large team of USDA-funded scientists has been tracking the distribution and impact of BMSB for several years. If you have information helpful in updating their current map (shown here), they can be reached at: STOPBMSB.org

Initial reports of BMSB establishment in an area are usually when they invade buildings to overwinter. Problems associated with them being an agricultural pest occur later. Unlike the Asian lady beetle, which is considered a friend of gardeners, the brown marmorated stink bug is a devastating pest of agriculture. Crops impacted include soybean, corn, wheat, tomato, peppers, beans, squash, pecan, peach, pear, apple, citrus, cherries, berries and grapes. The bugs also feed and develop on hundreds of species of woody trees and shrubs. The list of favored hosts includes some of the most common plants in the landscape — maple, oak, ash, redbud, serviceberry, pear, crabapple, cherry, honey locust, hawthorn, lilac, etc. These ornamental hosts are capable of supporting large numbers of stink bugs in late-summer that subsequently invade buildings to overwinter.

DESCRIPTION & HABITS. Stink bugs are related to bed bugs, but do not bite humans; their elongated, piercing mouthparts are used only to suck nutrients from plants. Their name comes from the pungent, cilantro-like odor produced by scent glands located on the mid-section of the body.

Hundreds of different species of stink bugs occur in North America, but only a few invade and overwinter in buildings. Most varieties are green, gray or brown and the adults, the stage entering buildings, have a shield-shaped body. BMSB adults are comparatively large —about 5/8-inch in length— and distinguishable from other stink bugs by white and black banding on their legs, antennae, and around the edge of the abdomen. The term ‘marmorated’ means having a marbled or streaked appearance. If a number of stink bugs are appearing indoors, chances are that BMSB is the culprit. Confirmation is important, however, since it is easy to confuse them for other pests.

Adult brown marmorated stink bug. Note the light and dark banding on antennae, legs and abdomen

(Photo: R. Bessin, UK Entomology)

Boxelder bugs (top) and some leaf-footed bugs like the Western conifer seed bug (bottom)

also enter buildings in the fall and are sometimes mistaken for stink bugs.

As noted earlier, BMSB attacks a wide variety of plants. They often feed by inserting their piercing mouthparts into fruits and seeds, damaging the marketability of many crops. Consequently, the pests are a serious threat to agriculture. BMSB also harm trees and shrubs in commercial nurseries and residential landscapes. Besides injuring berries, seeds, stems and foliage, the bugs may feed directly through the trunk, releasing sap, which attracts nuisance ants and wasps.

Stink bugs damage many crops, including apples and soybeans (Photos: R. Bessin, UK Entomology)

Stink bugs lay their eggs outdoors on the underside of host plant leaves. The newly emerged nymphs are reddish and black in color, becoming brown as they mature. The telltale white and dark banding on legs and antennae of adults is also apparent on the nymphs. Average development time from egg to adult is about 30-45 days. One to two generations per year occur in northern and Midwestern states, while additional generations are possible further south. BMSB adults are quite mobile. They readily fly from one landscape to another and between agricultural, urban and forested areas in search of preferred host plants. These environments also afford overwintering habitat crucial for their survival.

OVERWINTERING WITHIN BUILDINGS. Brown marmorated stink bugs prefer to hibernate in cool, dry, protected places. Cracks and voids within buildings fulfill these needs perfectly. Favored overwintering sites in nature include rocky outcroppings and standing dead trees with loose, thick bark such as oak and locust. The bugs do not overwinter in shrubs, mulch or leaf litter, which are generally too moist for their survival. Substantial mortality of BMSB occurs when winter temperatures routinely fall below 10⁰F. Conversely, mild winters foretell of large population increases as the seasons progress.

The ‘urge’ to overwinter is triggered by decreasing day length and temperature. Late in the summer, adults congregate in large numbers on favored host plants. When the aggregations occur close to buildings, subsequent movement indoors is likely. Dwellings in wooded and agricultural areas are especially prone to stink bug invasions, as they are to invasion by lady beetles. Similar to lady beetles, adult stink bugs move to buildings on warm sunny days in September and October.

Flight activity tends to be greatest in the afternoon and may vary in intensity from one day to the next. After the bugs alight, they seek out protected places to spend the winter. Common entry points include cracks and gaps around windows, doors, roof flashing, vents, window air conditioners, fascia and siding. They tend to prefer upper areas of buildings, often entering via attics and chimneys. A similar preference for higher locations occurs in nature, where the bugs choose upright trees over fallen ones and ground litter.

Buildings in poor repair with many cracks and openings are most vulnerable to infestation. In such cases, stink bugs may enter by the thousands. Overwintering locations include crevices, walls, ceilings, and attics affording cool, dry refuge. Unheated attics are often the most crucial overwintering location inside buildings; crawlspaces and basements are much less preferred. Stink bugs also overwinter in garages, outbuildings, vehicles, HVAC units, gas grills, etc.

More than 500 stink bugs collected over two days from a home (Photo: R. Bessin, UK Entomology)

During winter and early spring, stink bugs again become active, accessing living areas through cracks, vents, fireplaces and other openings. While the overwintering habits of BMSB and Asian lady beetles are similar, there are some differences. Stink bugs begin entering buildings earlier in the fall —in Kentucky, early-mid September, vs. October/November for lady beetles. Stink bugs also tend to be more active indoors throughout the entire winter, especially on warmer days. Occasionally they may be found on houseplants, possibly feeding, in late winter. The bugs emerge from hibernation from March to May and resume living outdoors. They typically require a few weeks of feeding on host plants before mating and egg laying.

IMPACT ON HUMANS. Stink bugs are solely plant feeders and do not bite humans or pets. The adults overwinter in an unmated condition and do not breed or reproduce indoors. Consequently, those spotted during the winter are the same individuals that entered the previous fall. Nonetheless, householders tend to be much less tolerant of stink bugs than they might be of lady beetles, which are smaller, more recognizable, and better understood. BMSB are attracted to light and may buzz around lamps and light fixtures in the evening. In late-summer/fall, the bugs are also attracted to porch lights, late-night convenience stores, service stations, manufacturing plants, etc. Similar to bed bugs, their fecal spotting can stain walls, curtains, and other surfaces.

Besides being a nuisance, stink bugs emit a pungent odor similar to cilantro when picked up or disturbed. When crushed, squeezed or handled they often excrete chemicals irritating to the skin. People disposing of stink bugs should use paper towels or tissue when handling them, and avoid touching their face or eyes. Recent clinical studies also suggest BMSB may be an important airborne allergen to people. Individuals plagued by stink bugs may suffer irritation and inflammation of the eyes and nose, similar to the reaction some have from exposure to the Asian lady beetle. People experiencing such symptoms in dwellings with many stink bugs should consult their physician.

MANAGEMENT. Management options are similar to those for other fall invaders, but there also are other important considerations, outlined below.

Indoor removal. The best way to remove stink bugs indoors is by hand (with gloves or tissue, per the point above about irritating secretions), or with a broom or vacuum. Disturbed bugs are likely to release an odor, so brooms and vacuums may smell like stink bugs for a while before the odor dissipates. A cut-off nylon stocking can be used in the suction tube of the vacuum to limit odor and conserve bags. Large collections may warrant disposal of the entire vacuum bag and aeration of the hose. Stink bugs immediately drop from vertical and overhead surfaces when disturbed. Small numbers of bugs residing on walls, ceilings, drapes, lampshades, etc. can be dispatched efficiently by placing a container underneath and gently prodding them to drop off.

Sealing Entry Points. Sealing cracks and openings is the most permanent way to prevent stink bugs and other fall invaders from entering buildings. Summer is the best time to do this, before they begin entering buildings to overwinter. Despite their relatively large size, adult BMSB are thin-bodied and able to fit into surprising tight spaces. Cracks should be sealed around windows, doors, soffits, fascia boards, pipes, wires, etc., with caulk or other suitable sealant. Don’t buy a cheap caulking gun. Features to look for include a back-off trigger to halt the flow of caulk when desired. Silicone or silicone latex caulks that dry clear are easier to use than pigmented ones because they hide mistakes.

Repair damaged window screens and install screening behind attic vents, which are common entry points for stink bugs. Trials by our group indicate that conventional-sized, galvanized mesh hardware cloth is ineffective for excluding brown marmorated stink bugs. When adults were challenged with ½ and ¼-inch diameter mesh screening, 100% and 50% of bugs, respectively, were able to pass through the openings. Mesh sizes of 1/6 or smaller were required to keep the adult stink bugs out. Also seal or remove window-mounted air conditioners in the fall, as these are another common entry point for stink bugs.

Attics are common entry points for stink bugs. Effective screening requires a mesh size no larger than 1/6-inch.

Traps. Pheromone-laced aggregation traps are being deployed for detection of BMSB and monitoring their levels in agriculture. Unfortunately, the same traps are ineffective at attracting stink bugs during their overwintering period within buildings. Similar to lady beetles, stink bugs are strongly attracted to ultraviolet light. Consequently, glue board-based light traps can be useful for harvesting these pests in areas such as attics. Householders can fashion their own stink bug trap by positioning a light above a large pan of soapy water.

Insecticides. Insecticides are not warranted for controlling stink bugs indoors, except perhaps in heavily infested areas such as attics. Efforts to kill overwintering stink bugs in wall cavities is unlikely to be successful, and could exacerbate problems with carpet beetles and other dermestids feeding on accumulations of dead insects.

If stink bugs are a perennial problem, householders may want to hire a professional pest control firm. Many companies apply insecticides to building exteriors in the fall, which helps prevent pest entry. Fast-acting residual insecticides can be sprayed into crevices and as a targeted band around windows, doors, eaves, soffits, attic vents, chimneys, and other likely points of entry. Some of the more effective insecticides used by professionals include Demand (lambda cyhalothrin), Suspend (deltamethrin), Talstar (bifenthrin) and Tempo (cyfluthrin). Effective over-the-counter versions of these products include Ortho Home Defense, Spectracide Bug Stop/Triazicide, and BioAdvance Home Pest Killer. Purchasing these products in concentrated (dilutable) form will allow larger volumes of material to be applied with a pump-up or hose-end sprayer (read and follow label directions carefully). As with other fall invaders, the key is to initiate treatment before the bugs begin gathering on buildings to overwinter — early-mid September in the Midwest but somewhat variable by locale. Such application would probably need to be repeated at least monthly during the extended flight period of stink bugs to buildings. During late winter or early spring, barrier treatments are ineffective since the pests gained entry the previous autumn.

While BMSB can feed on hundreds of different host plants, certain varieties in the landscape are preferred. Examples include redbud, maple, honey locust, serviceberry, crabapple and cherry. Such favored hosts can be monitored in late summer, before the pests begin moving to nearby buildings. Companies licensed to treat trees and shrubs in the landscape can also preemptively spray aggregations of stink bugs staging in these areas near dwellings.

FUTURE PROSPECTS. Like many invasive species entering the U.S. from abroad, the brown marmorated stink bug is expected to worsen over time. Fewer natural enemies (predators, parasites, pathogens) occur in this country to keep BMSB populations in check. A tiny wasp that attacks BMSB eggs in Asia has also been discovered in the U.S., and may provide some relief in the future. In the meantime, there is no simple way to prevent stink bug invasion of buildings. Vacuuming, pest proofing and properly timed exterior applications can provide relief, but require effort.

Issued: 9/20

CAUTION! Pesticide recommendations in this publication are registered for use in Kentucky, USA ONLY! The use of some products may not be legal in your state or country. Please check with your local county agent or regulatory official before using any pesticide mentioned in this publication.

Of course, ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW LABEL DIRECTIONS FOR SAFE USE OF ANY PESTICIDE!

Photos: © M. Potter & R. Bessin, University of Kentucky Entomology